- Key insights: Credit unions are adopting employer-sponsored small-dollar lending as a way to gain new retail and commercial customers. For banks, it can also mean Community Reinvestment Act credit.

- What’s at stake: Short-term liquidity products like earned wage access have gained popularity among consumers, and some financial institutions see opportunity in the space.

- Expert quote: “Earned wage access is really good when you need a spot. … Employer-sponsored small-dollar loans are better when you have either a larger emergency or larger expense,” Sara Wasserteil, program director at the Corporate Coalition of Chicago, told American Banker.

It’s a lending program born on the back of a napkin.

Processing Content

Eighteen years ago, the head of human resources for a Burlington, Vermont-based cookie dough manufacturer sat down with Bob Morgan, now the CEO of $1.1 billion-asset North Country Federal Credit Union, to find an

Rhino Foods was in a predicament. Many of its employees didn’t have access to traditional banking, and they were coming to Rhino’s HR department to get advances on their pay. But Rhino needed a more permanent solution.

“Our CEO literally wrote on the back of a napkin, and said, ‘Let’s do this,’ and that was the foundation for this program that we’ve been a part of for 18 years,” North Country’s Senior Vice President of Lending Jeff Smith told American Banker.

It’s called employer-sponsored small-dollar lending, or ESSDL, and it is designed to help bridge unexpected expenses. It’s also seen as a potential

How the program works

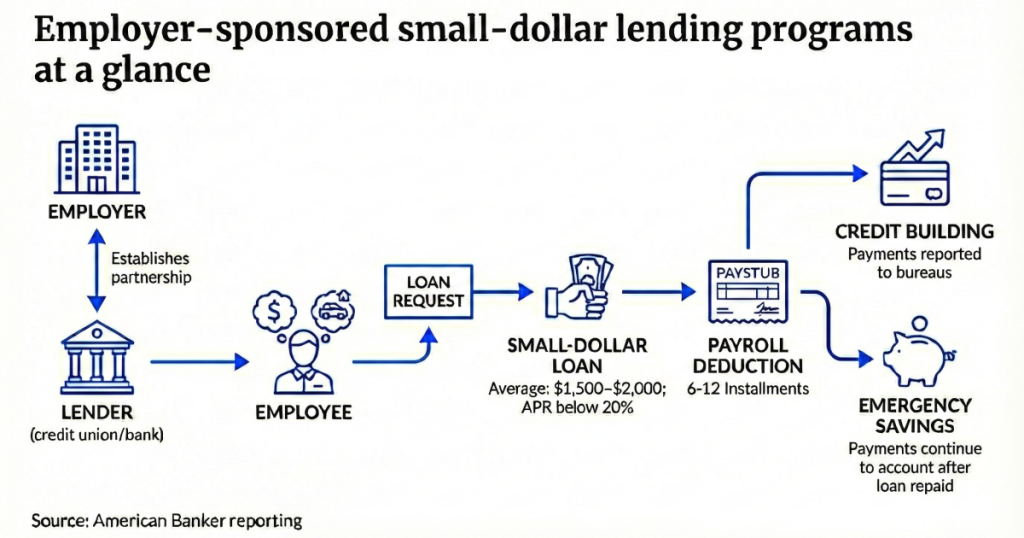

For ESSDL, companies partner with a credit union or bank to provide access to same- or next-day cash for their employees. There are no credit checks. Instead, employers vouch for their employees by paying a set-up fee and an additional fee based on utilization and loan performance.

“The premise of the program is that the employer is creating a relationship with a local lending institution and vouching for the employee and saying, ‘This is someone that works for me, that’s in good standing. If you extend them as credit, I will help to facilitate the repayment,'” Christina Blunt, executive director of the Rhino Foods Foundation, told American Banker. The Rhino Foods Foundation is a two-person subsidiary of Rhino Foods charged with helping lenders and businesses stand up ESSDL programs across the country.

The loans cap out anywhere between $1,500 and $2,000, depending on the lender, and are repaid in six to 12 installments of $50 to $60 through a payroll deduction. Annual percentage rates are capped at 20%, and once the loan is repaid, payments continue – so long as the consumer doesn’t opt out – into a newly created emergency savings account.

Payments are also reported to credit bureaus, which can help to improve credit scores and lead to new lending opportunities in home or auto.

North Country works with more than 50 companies within its field of membership, and has originated 12,000 small-dollar loans, totaling about $15 million, Smith said.

“If we can support a marginalized population in helping them access affordable, small-dollar credit to prevent emergencies or to navigate emergencies, it’s helping them,” Smith said.

The loans do hold a higher average delinquency rate when compared to the rest of North Country’s portfolio at about 4%, but that’s a drop in the bucket, according to Smith.

“All of those loans don’t equate to more than $550,000 on our balance sheet,” he said. “Within our loan portfolio of $83 million, a half-million dollars is nothing.”

Why now?

Small-dollar loans are not a new product, but have gained steam more recently. Banks and credit unions were hesitant to offer small-dollar loans because they are far from the most profitable way to deploy capital. But proponents of the program say it offers financial institutions a key customer acquisition channel for both retail and commercial customers. And for banks, small-dollar lending can also offer Community Reinvestment Act credits.

“If we do our job right, what we’re then doing is we’re bringing in a new member, and at that point, we have the ability to talk to members about other products and services, and we can then make them a full fledged member,” Smith said, noting the same goes for commercial clients.

“The commercial relationships are where the dollars are and where they can have the most bang for their buck,” Smith said.

The customers are also “really sticky,” Blunt said. “They pay off their loans, and they don’t close their accounts. They become very, very loyal customers.”

And for employers, the benefits of offering small-dollar loans are similar to offering earned wage access: It facilitates employee retention, and promotes stronger talent attraction.

“The view on this was when employees are financially doing better and have access to safe and affordable resources, then that also means less work interruptions, lower turnover for employers, those types of things, Jane Doyle, senior regulatory policy associate at Chicago-based consumer advocacy group Woodstock Institute, told American Banker. The Woodstock Institute has been promoting the program with lenders and businesses in the Chicago area.

Gaining new traction

The program has been growing in Vermont for more than a decade, and is spreading to New England, New York and Chicago thanks to interest from community and consumer advocacy groups, Chris Hynes, Rhino Foods’ income advance program manager, told American Banker.

“We’ve partnered to support the build out at about 12 lenders,” Hynes said. “Southern California is coming on as a hub as well too.”

The foundation relies heavily on community champions to help spread the word about the program. In Southern California, soap company Dr. Bronner’s has been a key steward in pushing the program, and in Chicago, the Woodstock Institute and the Corporate Coalition of Chicago, an alliance of more than 50 companies, have been actively promoting the program.

“One thing that we had identified was that there was not a very good option for individuals with low or no credit when they had an emergency or when unexpected expenses arrived,” Sara Wasserteil, program director, Corporate Coalition of Chicago, told American Banker. “We believed that there was hopefully a market based solution for this, versus just letting people go high and dry.”

Proponents of the program say it doesn’t replace other finance products such as earned wage access or early pay that have been recently popularized by fintechs, but rather is a better alternative to unexpected expenses.

“Earned wage access is really good when you need a spot, ‘I need money that I can afford, I just need it a little bit earlier,'” Wasserteil said. “Employer sponsored small-dollar loans are better when you have either a larger emergency or larger expense.”

But some credit unions do see earned wage access encroaching on its ability to offer small-dollar loans.

Rochester, New York-based Genesee Coop Federal Credit Union is in the process of launching its own ESSDL program, Dan Apfel, the credit union’s CEO, told American Banker. Genesee backed a New York State bill that would

“For years, we’ve offered relatively low-cost lines of credit. We also try to provide financial education,” Apfel said. “There are people who need money and feel like it’s easier to get it from an online lender than it is to go ask your parents or go ask a friend. The problem is they get stuck in cycles of debt.”

North Country and Rhino hope more lenders will adopt the program now that they’ve nailed down the program design process.

“What we try to help [lenders] do is to design a program that will have a huge amount of upside in the long run in terms of client acquisition, so not just CRA and community impact,” Blunt said.

“We don’t want our lending partners to design this to be a charitable endeavor, because then it will surely be a loss leader. What we want is for them to be really deliberate about this as being a way to steward new clients or new members and to grow their financial capacity along with that right client relationship,” she said.

But they’re also hoping that it allows lenders to further entrench themselves in their communities, Smith said.

“When people are struggling more now than ever, having affordable access to small-dollar credit is vital,” Smith said.