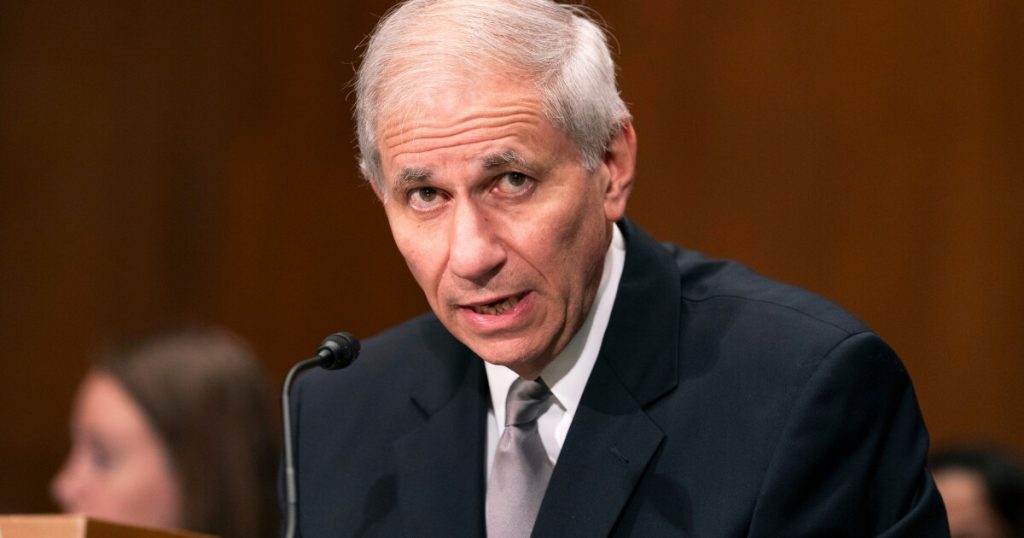

WASHINGTON — Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. Chair Martin Gruenberg warned that deregulatory efforts in the past have often created the conditions for financial crises to emerge, and suggested that the similar deregulatory push by the incoming Trump administration could yield similar results.

In a

“As I leave the FDIC, I thought there might be value in sharing some of the lessons of that experience as we head into a period of uncertainty about the future path of financial regulation in the United States and globally,” Gruenberg said. “In particular, I offer the observation that while innovation can greatly enhance the operation of the financial system, experience suggests it be tempered by careful and prudent management and appropriate regulation and supervision.”

Gruenberg said the passage of the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act in 1980 and the Garn-St. Germain Act in 1982 lifted some of the Depression-era limits on interest rates banks and thrifts could pay depositors and sanded down other safeguards on thrifts meant to make them more competitive. The result of that innovation was the Savings and Loan Crisis, in which hundreds of banks failed when interest rate changes put their portfolios underwater.

“While certain deregulatory measures were appropriate for the thrifts to navigate their interest rate-induced losses, it is clear in retrospect that the manifestation of risk in one area cannot be dealt with by deregulating other types of risk-taking,” Gruenberg said. “Moreover, in a deregulatory period, strong and effective supervision is indispensable.”

Similarly, the push in the late 1990s to end the Glass-Steagall prohibition against the mixing of investment and commercial banking was meant to foster innovation, and led to an era of combination in the banking industry that led to the creation of many of the Global Systemically Important Banks that dominate the industry today. But the commingling of commercial banking and the advent of more complex offerings like collateralized debt obligations and derivatives trading made the job of supervising bank holding companies far more difficult, which made the ultimate meltdown of the U.S. housing market impossible for the banking industry to withstand on its own and harder for regulators to avoid proactively.

“Modest attempts to curtail risky lending activities through regulatory guidance were met with significant resistance from the industry and Congress. Such efforts were often thought to stifle innovation,” Gruenberg said. “As the mortgage market became over-extended, continued demand for highly-rated assets and declining demand for the riskier tranches of mortgage-related securities incentivized financial engineering of new products — such as collateralized debt obligations, CDO-squared, synthetic CDOs, and credit default swaps — that fueled the demand for continued securitization of non-prime mortgages. At the time this financial engineering was considered a form of innovation.”

The failures of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank and First Republic in the spring of 2023 could also find their antecedents in deregulatory efforts by Congress. The passage of the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act in 2018 raised the asset threshold for banks’ enhanced prudential standards spelled out in Dodd-Frank from $50 billion to $100 billion, leaving the Federal Reserve wide latitude to apply those standards to banks with between $100 and $250 billion of assets.

The application of that law led to many banks between $100 billion and $250 billion of assets not having to submit resolution plans to their regulators, comply fully with the liquidity coverage ratio or undertake company-run stress testing, which Gruenberg said could have given supervisors more of a chance to head off the banks’ failures before it was too late.

“The deregulatory environment of the time did not help. Silicon Valley Bank would not have been in compliance with the full Liquidity Coverage Ratio as it had been applied prior to the implementation of the 2018 law,” Gruenberg said. “It was not required to undertake company-run stress testing, and the transition rules under the 2018 law delayed its supervisory stress test despite its rapid growth. Its holding company was not large enough to require a Title I resolution plan. The 2018 law also had a chilling effect on supervisors at the time, as documented in the Federal Reserve’s analysis of the SVB failure.”

Gruenberg’s remarks are a marked contrast with those given by his likely successor, FDIC Vice Chair Travis Hill, last week. In

“A much better approach would have been — and remains — for the agencies to clearly and transparently describe for the public what activities are legally permissible and how to conduct them in accordance with safety and soundness standards,” he said. “And if regulatory approvals are needed, those must be acted upon in a timely way, which has not been the case in recent years.”

Gruenberg is slated