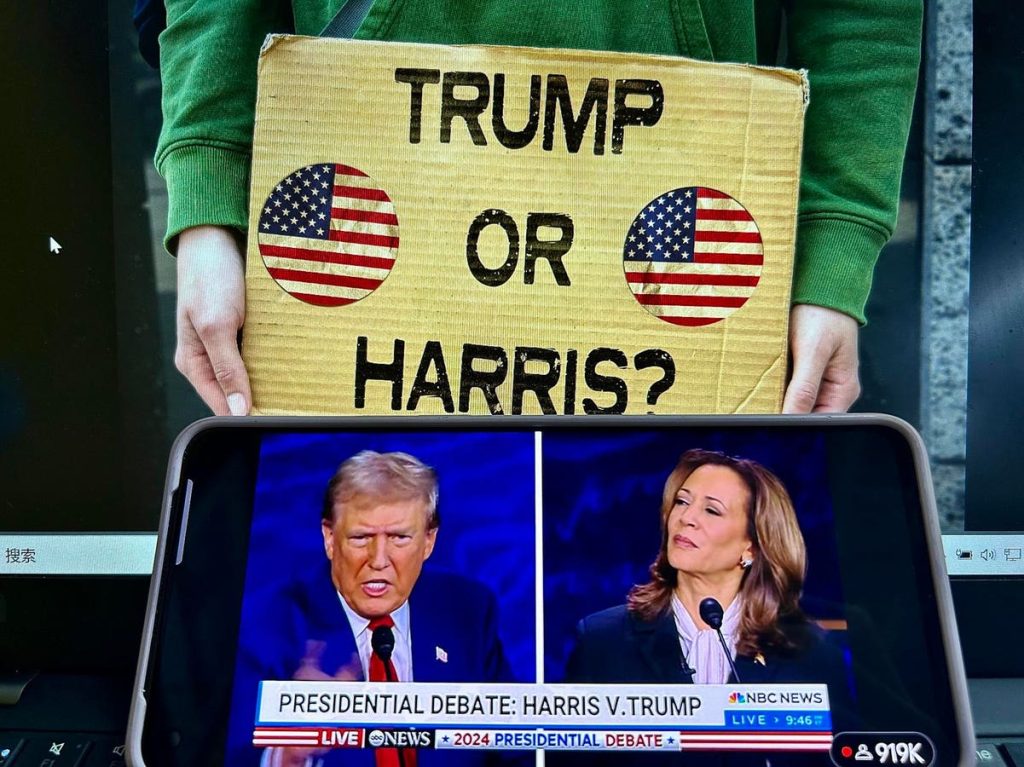

BEIJING, CHINA – SEPTEMBER 11: A smartphone screen shows the live broadcast of presidential debate … [+]

For decades, the desperate need for government to help support middle-income frail older adults, younger people with disabilities, and their family members has been clear. Until now, lawmakers largely have done nothing about it. But that finally may be changing.

Vice President Kamala Harris, the Democratic nominee for President, has proposed an ambitious expansion of traditional Medicare that would, for the first-time, cover some long-term supports and services focused on care delivered at home. Former President Donald Trump, her Republican opponent, has countered by promising a family caregiver tax credit.

While Harris’s proposal leaves out key specifics and Trump has offered no details at all, the idea that both candidates feel the need to talk about long-term care is a major step forward.

The fate of federal long-term care reform will largely depend on the outcome of the coming election. But here’s a quick look at the pros and cons of several designs:

A Medicare long-term care benefit: A big advantage of a Harris-like plan is that it would build on Medicare, which is hugely popular and well-established. But Medicare is fundamentally a health insurance program, and not designed to provide personal care and social supports.

Another downside: Beneficiaries likely would be able to purchase only limited services and their care choices would be constrained by complex rules.

It appears that Harris would fund her plan through general tax revenues. This would help hide the true cost, but without dedicated funding, a Medicare long-term care benefit would be at great risk for repeal or future budget cuts. A Medicare-based program also raises difficult questions about how it would interact with Medicaid and private insurance.

An expanded Medicaid long-term care benefit: Medicaid is a well-established federal program that already provides health and long-term care. The cost is shared by the states and the federal government, Medicaid long-term care is available only to those with limited income and financial assets.

But Medicaid benefits and eligibility vary widely by state. In many, the amount and quality of care is limited. And like Medicare, it limits how its funds can be spent.

The biggest shortcoming: Medicaid would provide no support for middle-income people, who cannot afford to pay for care themselves, but have too many financial resources to be eligible for the program.

Front-end public insurance: Unlike Medicare or Medicaid, people with public long-term care insurance would have flexibility in the services and supports they purchase, especially if the program provides a cash benefit. Washington State already has enacted such a plan and other states, including California, are considering one. While front-end coverage would provide assistance to more than half of older adults, those with very long spells of need would run out of benefits well before they die, and many would end up on Medicaid.

Catastrophic public insurance: It would insure those who need care for a long period of time, such as those with dementia. It would substantially reduce Medicaid long-term care costs. And it would be a more comfortable fit with private insurance, since carriers prefer insuring front-end risk.

But fewer people would be eligible for benefits, and lawmakers generally dislike a broad-based tax that benefits relatively few people.

A caregiver tax credit: This would be just one of many tax credits already in the law, making it familiar to lawmakers. But would a credit of say, $1000, make any difference to those struggling to pay for care that costs tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars annually. Would the credit be available to low-income households, or just to those whose tax bills exceed the credit amount?

Trump would provide the credit to caregivers, not recipients of care, who most often pay the bills.

A credit also raises enormous administrative problems. If three siblings are caring for a parent, who gets the subsidy? How do you prove you are an eligible caregiver?

The current crop of ideas comes with a long backstory.

In 2010, Congress included a voluntary public long-term care insurance program as part of the Affordable Care Act. But it was doomed by its very voluntariness and the program was repealed before ever getting off the ground.

In 2019, Washington State enacted its public long-term care insurance program. It began collecting payroll taxes in 2023 and is scheduled to start paying benefits in 2026. However, an initiative to effectively repeal the program will be on Washington’s ballot next week.

In 2023, Representative Tom Suozzi (D-NY) introduced a federal long-term care insurance program called the WISH Act. While the Washington State law covers the first $36,500 of long-term care costs, WISH would cover true catastrophic needs—kicking in after a period of time but offering benefits for life.

So far, the bill has gotten little traction, but Suozzi plans to reintroduce it early next year.

Also in 2023, President Biden proposed increasing the federal contribution to Medicaid long-term care by $400 billion. Congress eventually enacted a far more modest version.

As the need for care grows, politicians finally are paying attention. It is no coincidence that both major party presidential candidates are talking about long-term care. The next step will be to see what they do about it.