An Obamacare sign at a Miami insurance agency on Nov. 12, 2025.

Joe Raedle | Getty Images

The White House on Thursday reiterated its support for sending payments directly to households to cover health-care costs, an idea President Donald Trump has championed for months.

However, health policy experts reached by CNBC said they were skeptical of the proposal.

“I do think it’s a bad idea,” said Gerard Anderson, a professor of health policy and management at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

The policy was part of a broad outline of a health-care plan that the White House said would lower drug prices and insurance premiums. In a video unveiling the framework, dubbed “The Great Healthcare Plan,” Trump called on Congress to swiftly codify it into law.

Trump has shown enthusiasm for sending direct payments in other contexts during his second term, floating ideas including tariff dividend checks.

It’s hard to assess the specific impact of direct health-care payments, experts said, since the White House framework lacked key details such as who would be eligible, the amount consumers might receive and how the money could be spent.

At a high level, it doesn’t appear the proposal would grant the same level of financial assistance for health care that consumers currently receive, which would likely lead many to drop their insurance and cause premiums to rise for remaining enrollees, Anderson said.

There would also have to be strong guardrails in place to dictate how people could spend their health-care funds, said Nick Fabrizio, a health policy expert and associate teaching professor at Cornell University’s Jeb E. Brooks School of Public Policy.

“I feel very strongly that if you give people money, they will spend it on things other than health care unless it’s like a voucher,” Fabrizio said.

Trump’s overall framework, which calls for policies like greater price transparency in the medical ecosystem, could succeed in lowering health costs, Fabrizio said.

Trump framework comes amid ACA subsidy debate

Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-NY, speaks at a press conference with other members of Senate Democratic leadership following a policy luncheon at the Capitol on Oct. 15, 2025.

Anadolu | Getty Images

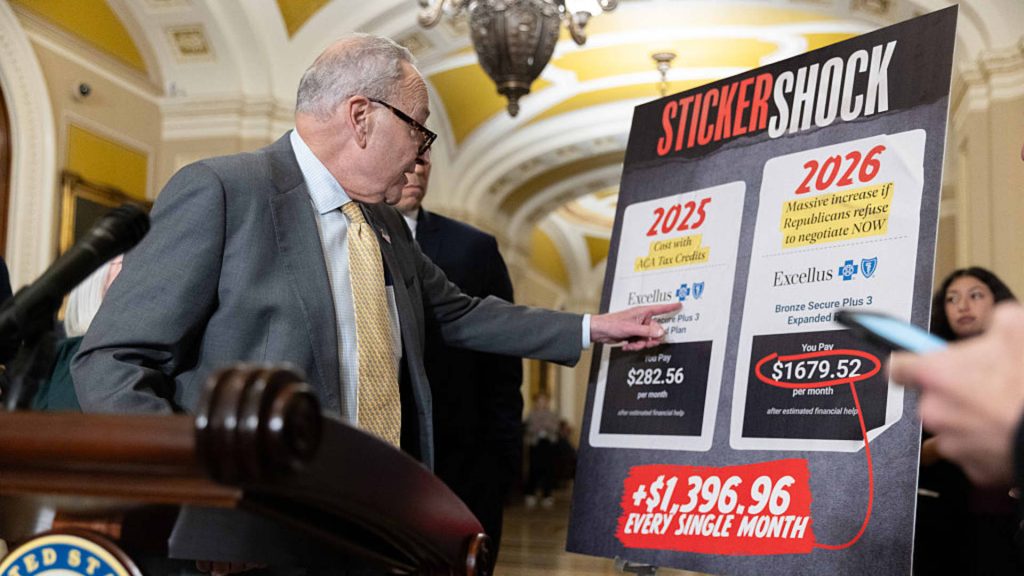

The framework comes as Congress is debating whether to extend enhanced subsidies that lower insurance premiums for millions of Affordable Care Act marketplace enrollees, and it may complicate a bipartisan effort underway to renew them.

Those enhanced subsidies, in place since 2021, expired at the end of last year. KFF, a nonpartisan health policy research group, estimated the lapse would cause premiums to soar more than twofold for the average recipient.

Without the enhancement, a baseline of subsidies known as premium tax credits is still in place for ACA enrollees.

Consumers can opt to receive those premium tax credits in one of two ways: in a lump sum during tax season, or via an immediate reduction in monthly insurance premiums.

In the latter scenario, by far the most popular, the federal government sends a consumer’s subsidy to their insurer, which then lowers the consumer’s upfront premium.

Trump’s health framework called for an end to “billions in extra taxpayer-funded subsidy payments” and instead supported sending that money “directly to eligible Americans to allow them to buy the health insurance of their choice.”

It’s unclear how such a plan would work, experts said.

Trump and some congressional Republicans had previously supported the idea of repealing some or all ACA subsidies and replacing them with contributions to health savings accounts or something similar, wrote Larry Levitt and Cynthia Cox of KFF. A health savings account is a tax-advantaged account geared to medical expenses.

A White House official said Thursday that consumers outside the ACA market would also qualify for direct payments.

While HSAs can be used to cover certain medical expenses, consumers can’t currently use them to pay insurance premiums — and only consumers who are enrolled in a qualifying high-deductible health insurance plan can make contributions to such an account, experts said.

“You’d have hurdles getting people through the door” and into an insurance plan if that HSA prohibition against premium payments were to remain, said Matt McGough, an Affordable Care Act policy analyst at KFF. “It’s really not going to relieve a lot of the [financial] burden for those people.

“The devil is really in the details here,” he said.

Amount is a key missing detail

The direct payment amount and the extent to which any remaining premium tax credits would be scaled back are other important, unknown details, experts said.

If the amount were not large enough, then younger, healthier people would generally be the ones to drop their coverage — leaving older, sicker enrollees behind, Anderson said. Insurers would raise premiums for the remaining insured to compensate for that risk, since older, sicker enrollees generally require more care, he said.

Legislation unveiled in December by Sens. Mike Crapo, R-Idaho, chair of the Senate Finance Committee, and Bill Cassidy, R-La., chair of the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, would provide an annual HSA contribution of $1,000 for individuals ages 18 to 49 or $1,500 for individuals ages 50 to 64.

That sum “really pales in comparison” to what many enrollees, especially those ages 50 to 64, had received from enhanced ACA subsidies, McGough said.

For example, the average middle-income 60-year-old earning almost $63,000 a year is no longer eligible for ACA subsidies, and is on the hook for the full, unsubsidized insurance premium in 2026 — about $15,000, according to a KFF analysis. In 2025, this same individual was eligible for an ACA premium subsidy of about $7,300.

Premium tax credit amounts vary greatly from person to person, based on age, income and geography.